As senior frontend developers and software engineers, we often find ourselves staring at a piece of code, asking the perennial question: "Do we fix this, or do we scrap it and start over?" It’s a challenge that transcends specific technologies and touches the core of software engineering – balancing immediate needs with long-term sustainability. The decision to refactor or rebuild is rarely clear-cut, involving technical debt, business priorities, team morale, and future scalability. This post will explore a framework for making that crucial decision.

Understanding the Spectrum: Refactor vs. Rebuild

Before we dive into the "when," let's clarify the "what."

- Refactoring: This involves restructuring existing code without changing its external behavior. The goal is to improve the internal quality, readability, maintainability, and efficiency of the code. Think of it as renovating a house – you're improving the layout, updating the plumbing, or adding insulation, but the house is still standing and functional throughout the process. It's often an ongoing activity, a part of daily development.

- Rebuilding (or Rewriting): This means replacing a significant portion, or even the entirety, of a system with new code. The external behavior might remain similar or evolve significantly, but the internal architecture and implementation are fundamentally different. This is akin to demolishing an old house and building a new one from the ground up. It’s a much larger undertaking, usually driven by critical flaws that refactoring can’t address, or by a need for a completely new foundation.

The Telltale Signs: When to Consider a Change

How do you know it's time to even think about this decision? Look for these symptoms:

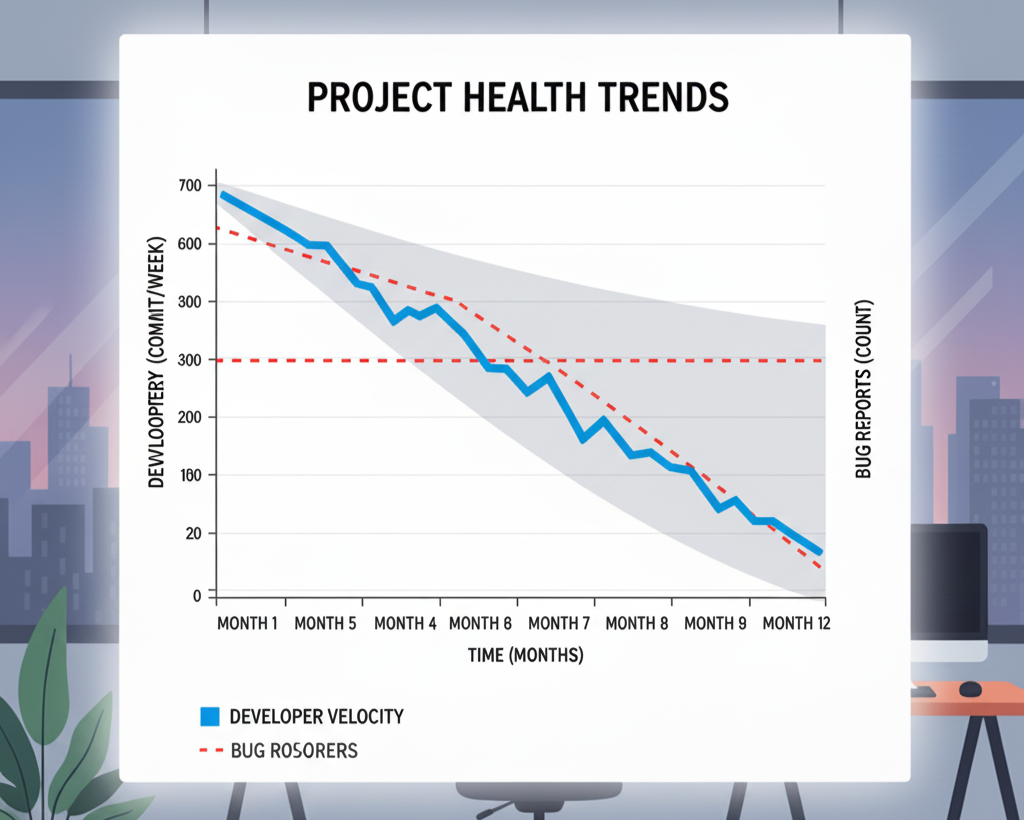

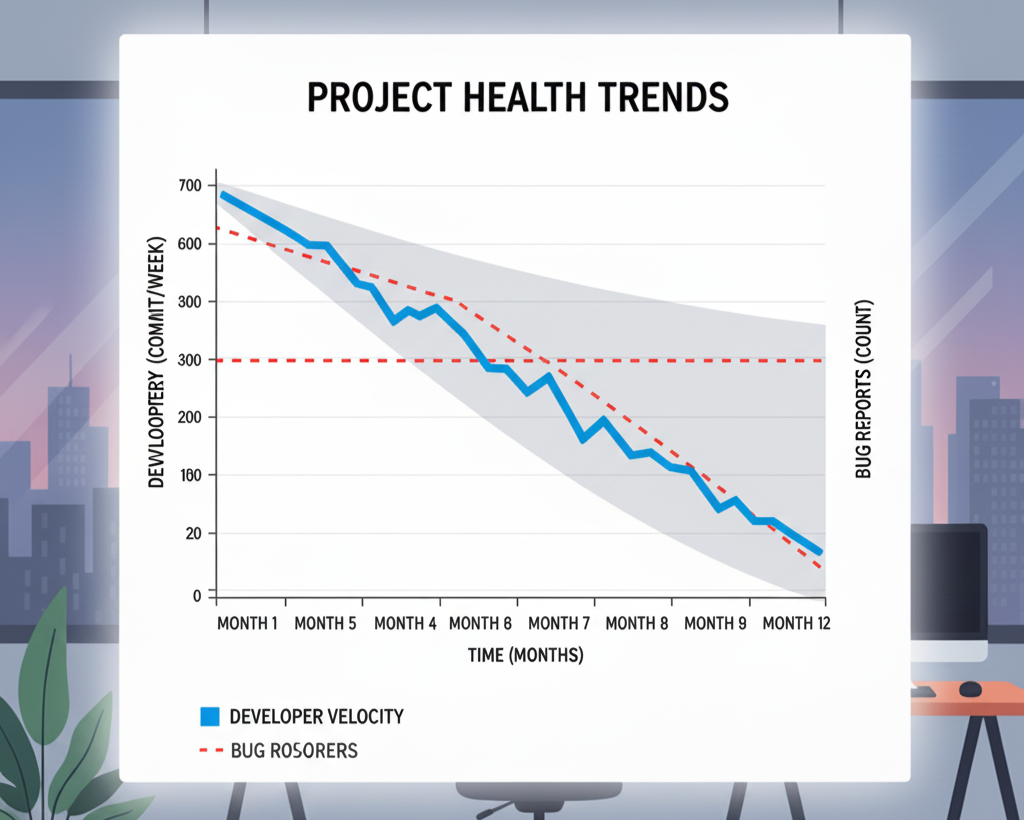

- Declining Velocity: Feature delivery slows down significantly. Simple changes take an inordinate amount of time, and bugs are introduced frequently. The team spends more time debugging existing code than building new features.

- Increased Bug Count: Even minor changes seem to break unrelated parts of the system. The "fix one, break two" syndrome is rampant.

- High Cognitive Load: New developers struggle immensely to understand the codebase. Even experienced team members find it hard to trace logic or identify impact areas.

- Scaling Issues: The existing architecture struggles to handle increased load, new data volumes, or complex business logic without significant performance bottlenecks.

- Obsolete Technology Stack: The underlying technologies are no longer supported, insecure, or are becoming a major hiring blocker.

- Lack of Testability: The code is so tightly coupled that writing unit or integration tests is nearly impossible, leading to a lack of confidence in releases.

The Decision Framework: Refactor vs. Rebuild

This is where the engineering judgment comes in. I use a multi-faceted approach, weighing technical factors against business impact.

Step 1: Quantify the Pain (The Technical Audit)

Before anything else, gather data. Objectivity is key.

- Code Metrics:

- Cyclomatic Complexity: High complexity often correlates with difficult-to-test and difficult-to-understand code.

- Code Duplication: Tools can identify repeated code blocks, a strong indicator of maintainability issues.

- Coupling & Cohesion: How tightly integrated are components? Are modules responsible for too many things?

- Test Coverage: What percentage of the critical paths are covered by automated tests? Low coverage means high risk.

- Build/Deployment Times: Are these becoming unacceptably long?

- Bug Reports & Incident Frequency: Track how often production incidents occur and how long they take to resolve.

- Developer Sentiment: Conduct anonymous surveys or hold open discussions. How frustrated is the team with the current codebase? What are their biggest pain points?

- Feature Delivery Metrics: How long does it take, on average, to ship a small, medium, and large feature?

Step 2: Business Impact Assessment

Technical problems are ultimately business problems. Translate your findings into business language.

- Cost of Inaction: What is the cost of NOT making a change? This includes lost revenue due to slow feature delivery, customer churn from bugs, increased operational costs (e.g., cloud bills, support staff), and reduced innovation.

- Opportunity Cost: What are the new features or market opportunities you're missing out on because your team is bogged down by technical debt?

- Risk Assessment: What are the security vulnerabilities or compliance risks posed by an outdated stack or unmaintainable code?

Step 3: The Fork in the Road - Refactor or Rebuild?

With data in hand, evaluate these scenarios:

Choose Refactor When:

- Targeted Pain Points: The problems are localized to specific modules or components, not endemic to the entire system.

- Known Solutions: You have a clear path to improvement for the problematic areas without fundamental architectural shifts.

- Maintainable Core: The core architecture is still sound, but parts have degraded.

- Continuous Improvement Culture: Refactoring can be phased in alongside new feature development, allowing for steady progress.

- Low Business Interruption Tolerance: The business cannot afford a long period without new feature releases.

- Strategy: Break down the refactor into small, manageable tasks. Integrate refactoring into sprint cycles ("20% refactor time"). Use techniques like feature flags to gradually roll out improved modules. Focus on high-impact areas first (e.g., slow pages, buggy components).

Choose Rebuild When:

- Systemic Failure: The issues are pervasive, affecting almost every part of the application. The current architecture is fundamentally flawed or can't meet future demands.

- Obsolete Foundation: The technology stack is beyond salvageable updates, posing security risks or making talent acquisition impossible.

- Significant Performance Bottlenecks: The current system simply cannot scale or perform adequately, even with optimization efforts.

- Vision Shift: The product vision has evolved so dramatically that the existing system is no longer fit for purpose, requiring a fundamentally different architectural approach.

- High Business Growth/New Market Opportunities: The potential gains from a superior new system far outweigh the short-term cost and effort.

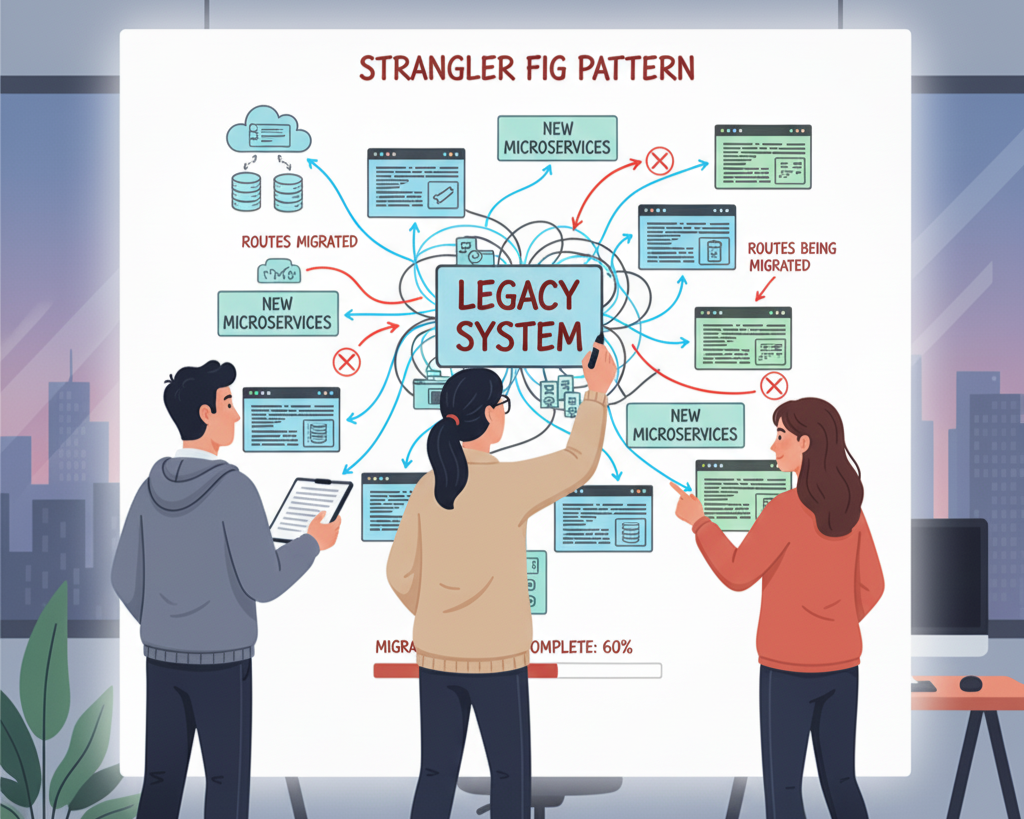

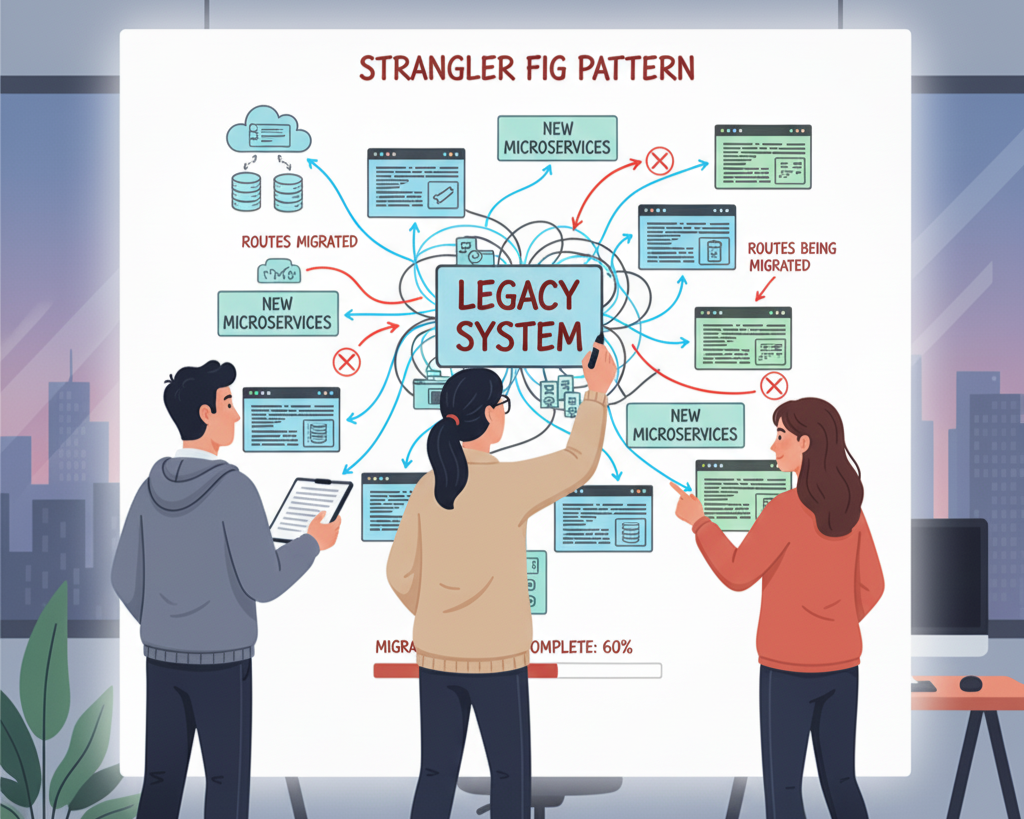

- Strategy: This requires a well-defined strategy. Consider a "strangler pattern" – building the new system piece by piece, routing traffic away from the old system incrementally. This minimizes risk and allows you to deliver value early from the new system. It also allows the old and new systems to coexist during the transition.

Presenting the Case to Non-Technical Stakeholders

This is a critical skill for senior engineers. Technical jargon won't cut it.

- Focus on Business Value: Translate technical debt into financial terms. "Slow development costs us X dollars in missed market opportunities each quarter." "Bugs lead to Y customer support hours and Z customer churn."

- Use Analogies: Explain the "house renovation vs. new build" analogy.

- Provide Options & Risks: Don't just present one solution. Offer the refactor path, the rebuild path, and the "do nothing" path, clearly outlining the costs, benefits, and risks of each.

- Transparency & Phased Plans: If a rebuild is chosen, emphasize a phased approach with clear milestones and expected interim deliverables. Highlight how this reduces risk and allows for continuous learning.

- Pilot Projects: For a rebuild, consider a small, non-critical component or a new feature that can be built entirely in the new stack to prove its value and gather early feedback.

Conclusion

The decision to refactor or rebuild is one of the most impactful choices a senior engineering team can make. It demands a blend of technical expertise, data analysis, and strategic business acumen. By systematically quantifying pain points, assessing business impact, and clearly communicating the rationale, we can guide our teams and organizations towards more sustainable, performant, and delightful software solutions. Remember, doing nothing is also a decision, and often the most expensive one.